Ah, you know, being a college art student is such an adventure! You've got that snazzy studio space to create your masterpieces, but it can feel lonely sometimes. I can't stress enough how crucial it is to have a mentor in your college art studio. They're like a lighthouse in a stormy sea of creativity!

Mentors, they're like these magical beings who guide you, give feedback on your work and help you network with other artsy folks. The hallmark of a good mentor is excellent listening skills balanced with professional experience and generosity. Having someone committed to providing quality and consistent feedback nurtures your creative present and future.

Let me tell you where to start if you're looking for a mentor.

First up, your professor; if there's a professor you genuinely admire and who knows their stuff about your preferred art form, they might be the mentor of your dreams! Ask if they can spare some time regularly to chat about your work and offer their insights.

Next is the college art gallery; those gallery staff members are usually eager to gab about art with students. If there's an artist or style you're really into, ask a staff member if they can point you toward a potential mentor.

And remember local artists! Your town or city is probably teeming with artists who'd be thrilled to mentor a budding college student. Check out local galleries and studios, and don't be shy—say hello to and regularly interact with the artists of your community. Having a mentor in your college art studio can be transformative for you creatively but also set you on a productive career path. So, reach out and ask for help!

My Mentors

During my college years at the Kansas City Art Institute, I was never shy about reaching out to professors. I was lucky in college, I had two great mentors who shaped my artistic practice profoundly: Wilbur Niewald and Shirley Luke Schnell.

Wilbur Niewald

Wilbur Niewald died this past spring at the age of 97. He live his entire life in Kansas City, and no one has painted the city as frequently as he did. His Plein air works could rightfully be called love letters to the city.

Wilbur earned bachelor and master degrees from the Kansas City Art Institute. He was a member of the painting faculty for 43 years, chaired the painting department from 1958 to 1985, and was a respected and well known painter throughout the United States.

In 1992, he retired. He remained devoted to his artistic practice and he spent hours each day, often six days a week, painting outdoors in Loose Park or the West Bottoms or in his studio during his retirement.

One of the things I liked to do when visiting Kansas City in the summer was to visit him while he was creating his Plein air artworks. I would find him passionately painting away at his easel near the tennis courts at Loose Park in Kansas City, Missouri, wearing his well-known attire: a straw hat, denim shirt, and blue jeans.

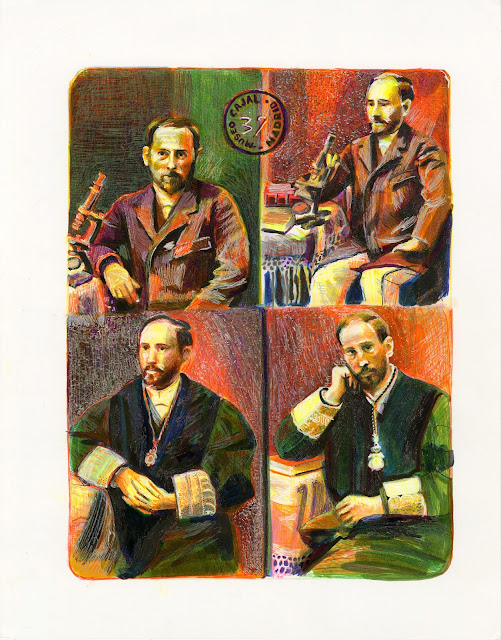

Above, a drawing I completed of Wilbur Niewald while he was painting in Loose Park during one of my visits to Kansas City, marker and pen on paper, 11" x 14."

I took Wilbur's drawing classes most semesters while I was in college. Every class was always the same, with one instruction: "Draw what you see." I found the experience meditative and relaxing, and I also developed a deep appreciation for working from observation.

Wilbur always took me seriously and respected me as an artist, which profoundly impacted me the most. I took myself seriously because of that. He understood my potential more than I did. As a sophomore, I had a conversation with him about switching my major from Painting to Fibers. He made a compelling argument to other faculty and me in the program about why I should not switch my major. I stayed because he convinced me.

He drew and painted from direct observation beginning in the 1970s. It never mattered to him what the condition of weather was. Once when our drawing class was outside drawing the landscape in Plein air, it began to rain. Most students began packing up and heading back to the classroom, but Wilbur exclaimed, "Don't leave; this is great. Change your drawing as the situation changes." He only convinced four of us to stay.

Above, a drawing I completed of Wilbur Niewald while he was painting in Loose Park during one of my visits to Kansas City, marker and pen on paper, 11" x 14."

Shirley Luke Schnell

There's nothing quite like a quirky art professor to get students excited about creativity. Shirley Luke Schnell was one of those teachers. With her whimsical, soft-spoken voice and eccentric clothing, she always seemed to be on the verge of levitating above all of us in the Foundations studio. But somehow, she always managed to bring unique and memorable insight to the studio practice, and her students always seemed inspired and to learn a lot.

Even though she was different than anyone else you'd ever meet, her students connected with and loved her. They knew that she cared about them and that she wanted them to succeed. She was always pushing them to be their creative limits with the concepts of her assignments. This generated growth and new perspectives on what is or could be.

Shirley is a true original, and in the classroom, she was the perfect example of how being different can be a good thing. After Foundations, I reached out to her for critiques of my paintings and help with my graduate school applications. She was fully invested and took time during her weekends to help me write my application essays with clarity. I was fortunate to have her mentorship after college, too. We became close friends, and she has been present for the significant milestones of my life. Such as visiting me in London during my residency at the Royal Academy of Arts and attending my wedding.

Above, a digital iPad drawing I created of Shirley during one of my visits to her home.

Embracing Change: The Journey with Alzheimer's

As we grow older, it's not uncommon for memory to fade, impacting both ourselves and our dear ones. When it comes to Alzheimer's, this shift can be particularly tough on relationships. I remember my incredible mentor, Shirley, who was officially diagnosed with Alzheimer's back in 2013.

Looking back, he signs were there even before her diagnosis—visible in her actions and words. Today, she's reached a non-verbal stage as the disease continues its progression. Though she's still with us, Alzheimer's has taken away so much. Let's cherish our memories and support those facing this journey.

1. Understanding Alzheimer's: A Battle of the Mind

Alzheimer's, one of the most common types of dementia, has touched the lives of over 5 million Americans. As a neurodegenerative disorder, it slowly erodes our memory and cognitive functions, making every day a struggle. Despite the efforts of researchers, the cause is unknown. Its cause is theorized to be a blend of genetic and environmental factors. The cure remains undiscovered.

2. Recognizing the Signs: Encountering Alzheimer's Symptoms

Living with Alzheimer's can be an incredibly personal and unique experience, as the symptoms manifest differently for everyone. Yet, some common threads bind these journeys: the challenges with memory, thinking, and communication and the shifts in mood and behavior.

Physical symptoms like trouble walking, dizziness, and appetite changes also make their presence known, adding to the daily battles faced by those with Alzheimer's.

3. How does Alzheimer's disease affect relationships?

Alzheimer's disease can be heart-wrenching, profoundly affecting our relationships with loved ones. Those with this condition might withdraw from socializing, struggle to recall names or faces, and even become disoriented or agitated. As friends and family, it's painfully difficult to watch someone we care for seemingly disappear from us.

But let's not forget that beneath the disease; their hearts are still capable of feeling love and affection. We must keep embracing them, even when communication becomes a challenge. Engage them in activities they've always loved, and practice patience and understanding. Together, we can make sure they never feel alone in their fight.

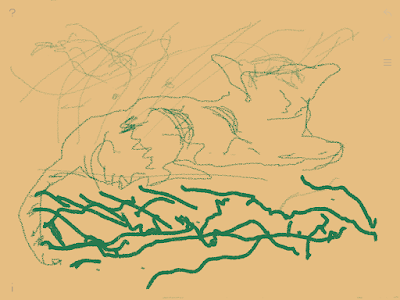

Above, a digital iPad drawing Shirley created, after the onset of Alzheimer's, of her cat during one of my visits to her home.

Loss

Losing a mentor—whether through death or illness is difficult.

Whether it hits you like a bolt from the blue or you see it coming, the passing of a mentor can feel like a shock. You may feel a great sense of emptiness after losing someone like the North Star guiding your ship, helping you grow and learn!

When a mentor leaves this world, it's easy to feel adrift and unsure. Let's remember that your mentor would want you to continue and keep growing creatively.

It is essential to pause, allow yourself to grieve, and then remind yourself that your mentor would be cheering you on to keep putting one foot in front of the other and pay it forward by mentoring a younger artist yourself!